Israel’s Bond Market Is Overlooked and Underallocated

Global allocators tend to assume that if a market is attractive, capital will naturally find it. In fixed income, that assumption can be wrong.

Israel’s bond market is a clear example: it is developed, liquid, transparent, and supported by large domestic institutions — yet it remains meaningfully underrepresented in global bond allocations.

This is not because the opportunity set is small or risky. It is because allocation decisions are driven by indices and plumbing, not by bottom‑up market quality.

1. A Credible Market That Looks Like a Developed Economy

Start with the basics. Israel is not an emerging market or an underdeveloped economy.

Israel is a strong developed economy, a full member of the OECD, with a robust financial sector and mature market institutions supported by comprehensive regulatory oversight. In fixed income, Israel has a strong history of public debt markets, a deep domestic investor base (pension funds and insurance companies), and active primary and secondary markets. Its bond market is further distinguished by an advanced exchange-traded structure, with transparent pricing and a centralized order book.

At the macro level, the Bank of Israel maintains an independent monetary policy that serves as a key stabilizing engine of the Israeli economy.

From a market-functioning perspective, Israeli government and corporate bonds behave much more like developed-market credit than emerging-market debt.

Yet global allocations do not reflect this reality.

2. Foreign Ownership: Low by Global Standards

One of the clearest indicators of underallocation is foreign ownership.

Compared with other developed markets:

Foreign ownership of Israeli government bonds is approximately 8%

Foreign ownership of Israeli ILS-denominated corporate bonds is approximately 1%

Domestic institutions dominate both government and corporate credit

Marginal pricing is set locally, not by global flows

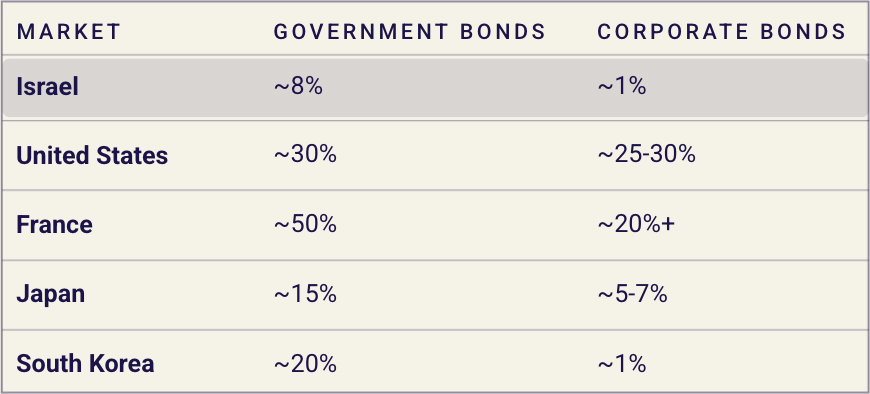

For context, a random sample of other major developed economies demonstrates how unusual this is. The below chart illustrates this point:

* Foreign ownership of government and corporate bonds by market (approximate, year-end 2025).

Against that backdrop, Israel stands out as an outlier across both government and corporate debt. Foreign ownership is low in absolute terms across the entire bond market — high single digits in government bonds and even lower in ILS‑denominated corporates — placing Israel near the bottom of the range among major developed economies. The takeaway is clear: compared with global peers, Israel has unusually low foreign ownership across both government and corporate bonds, leaving its bond market overwhelmingly driven by domestic institutions.

This pattern is not unusual for a market with mandatory pensions and a strong home bias. What is unusual is how little foreign capital is involved given Israel’s market size, liquidity, and level of development.

Low foreign ownership, in this context, is not a verdict on quality. It is a signal that global capital has not been structurally directed toward the market.

3. Index Inclusion (or Lack Thereof) Drives Allocation

The primary mechanism through which this structural underallocation occurs is global bond index construction.

Global fixed income indices serve as the core architecture of portfolio construction, shaping benchmarking, risk management, and the design of increasingly popular index‑based investment vehicles. As of early 2026, indexed strategies account for over 20% of global fixed‑income assets under management, roughly double their share in 2010.

As a result, most global fixed‑income portfolios are built from benchmarks.

If a country is under-weighted or excluded from major indices, it will be under-allocated in real portfolios — regardless of fundamentals.

Israel illustrates this clearly:

Israel represents approximately 0.27% of the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index, ranking 28th by country weight

Israeli ILS-denominated corporate bonds are excluded from major global corporate bond benchmarks, including the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Corporate Index

This exclusion is driven by index rules that prioritize USD and EUR issuance, minimum deal sizes, and international syndication and settlement conventions. Even allocators who “own the benchmark” therefore own little to no Israeli credit — particularly in corporates.

Israeli credit is not underallocated because of lower quality, but because it does not fit the rules embedded in global bond indices — and therefore does not naturally enter benchmark-driven portfolios.

4. Structural Frictions Matter More Than Fundamentals

Beyond indices, there are real — but solvable — frictions that continue to limit access to Israeli debt. These include local custody and settlement requirements, documentation and tax considerations, limited global research coverage, and general operational unfamiliarity. None of these challenges are insurmountable. But taken together, they raise the activation energy required for a global investor to engage.

In practice, this means that even when return potential, diversification benefits, and liquidity are attractive, capital does not automatically find the market.

5. Underallocation Does Not Mean Underdevelopment

It is tempting to equate low foreign ownership with market immaturity. In Israel’s case, that conclusion is backwards.

The bond market is supported by permanent domestic capital, deepened by decades of institutional participation, made transparent through exchange trading, and actively traded across cycles.

The reason it remains under-owned globally is not a lack of sophistication. It is a lack of representation in global allocation frameworks.

The Core Takeaway

Israel’s bond market is not overlooked because it is small or risky.

It is overlooked because:

Indices underrepresent it

Global plumbing does not naturally route capital toward it

Allocation decisions follow benchmarks, not market structure

In fixed income, opportunity does not guarantee allocation.

Understanding that distinction is the first step toward understanding why mispricings — and diversification benefits — can persist in plain sight.

About Kotel Investment Management: We serve as a bridge between U.S. capital and Israel’s overlooked fixed income markets, sharing insights and perspective through our research and thought leadership.

This content is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities.